The photo that set me on a course to becoming a biologist was published in 1965, but I didn’t see it until a few years later, when I was ten or maybe twelve years old. I’d been rooting through a stack of National Geographic magazines piled next to my grandparents’ television set. The picture shows a family of chimpanzees engrossed in mutual grooming. The oldest, a weathered female called Flo, purses her lips in concentration as she grooms her son. In the background a yard or two away, jotting notes in a field book, smiling a smile of soft delight at her subjects, is the young Jane Goodall. The chimps are relaxed, their backs to Goodall—her presence is accepted completely. It’s a serene scene, yet it’s packed with feeling and romance. I dreamed for years afterward of becoming a field biologist.

Looking back at that photograph, taken so many years ago by Hugo van Lawick, I marvel at how it triggered such strong emotions in a little girl. And how now, in adulthood, I remain captivated by images of wildlife that evoke a powerful response, from delight and wonder to horrified fascination. I’m moved by the quirky grace of courting birds, a mother elephant’s fearless protectiveness, the razor-edged focus of predators, and the desperate burst of the hunted in flight. Maybe I’m too sentimental to be hardnosed about pictures—but more likely, my reactions embody the power of images: above all, good photographs make us feel. And strong feelings create appreciation, compassion and urgency, which mold the choices we make as individuals and as a society. “We cannot win this battle to save species and environments,” wrote biologist Stephen Jay Gould, “without forging an emotional bond between ourselves and nature as well—for we will not fight to save what we do not love.”

If a central goal of photography is to spark feeling, we who focus on wildlife have an advantage among nature photographers: our subjects express their own emotions. The annoyed wolf snarls and lunges at her mate; the chimpanzee mother tickles her baby and evokes a laugh; the snowy egret erects his plumage in a display of feathery charm. Our subjects shout their feelings, through actions rather than words. Some of these behaviors relay simple emotions like fear; others seem to reflect complex mental states like apathy, curiosity, or consternation. But when we observe animals, do we really understand what they are experiencing? And perhaps as importantly—does it matter? How does animal expressiveness shape the emotional impact of a photograph, and what feelings do we bring to the image ourselves, as photographers and as viewers of pictures?

For years, scientists and philosophers doubted that animals experience emotions, apart from simple sensations like pain. By contrast, any dog owner will tell you that her dog feels joy, frustration, even grief. Perhaps the most compelling evidence for animal emotions is neurological: all mammalian brains contain the neural circuits that generate emotions. Indeed, these circuits are among the most ancient in the brain—we humans didn’t evolve our emotional capacities from nothing, particularly given the importance of feelings in forming relationships and caring for offspring. That said, brain circuits for emotion in animals are certainly wired differently than our own. Specialized neural hardware enables an eagle to detect a rabbit nearly a mile away, and allows an elephant to hear ultra-low frequencies of sound. Similarly, the startled, fearful responses of horses to the unusual is hardwired: as prey animals, fright and flight have enabled their survival.

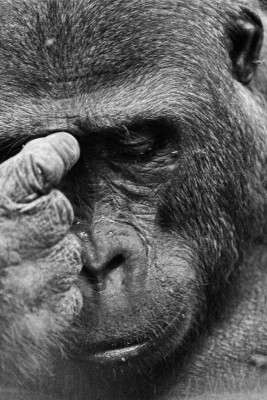

Like other primates, we humans use our faces to express our feelings. We lift our eyebrows, grin and bare our teeth, wrinkle our foreheads, and avert our gazes. The faces of our brethren are no less engaging. Over a period of ten minutes, the facial expressions of a mountain gorilla can range from disapproving to pensive to sweet to distraught. In my experience, capturing these expressions in a photo is a matter of being there and taking the picture—but interpreting their meaning is another matter.

We use several strategies to decipher the emotions that flicker across animal faces. In the case of mountain gorillas, our evolutionary close cousins, we tend to rely on empathy: a yawn conveys boredom, a stare might be threatening, a mother’s gaze expresses love and concern. With less closely related animals, personal experience often guides interpretation. If a mountain lion curls her lip into a snarl and I remember the face of a cat who tried to bite me, I surmise the lion is annoyed. But in many cases, expert information is needed to interpret expressions. In Tanzania, I watched a dominant chimp pursue an estrus female, slapping and screaming at other males as he ran. I photographed one of those other males, sitting still amidst the mayhem, mouth opened wide. Lips pulled back, the subdominant male bared huge canine teeth in an expression I found hostile and threatening. But when I showed my photo to Lisa Parr, an expert on chimp facial expressions, she explained that this was actually a “silent scream,” an expression of fear that helps appease a bully.

Any of the strategies above can lead to mistakes in interpreting animal emotions. After all, you and I have no real insight into what a mountain gorilla is thinking. Domestic cats and mountain lions may express their feelings differently, and we might not be able to find an expert to decipher our photos or memories. How then are we to accurately interpret the emotions of animals? How are we to sidestep the danger of anthropomorphizing—of misinterpreting our subjects from our limited, human point of view?

The bottom line is: we can’t.

In 1974, the philosopher Thomas Nagel published a landmark essay called “What is it like to be a bat?”, in which he wrestled with whether it’s possible to understand the mental state of an animal that navigates the world using a built-in sonar system. His answer is that we can learn about echolocation and imagine what it might be like to be a bat, but we can never know. It simply isn’t possible to comprehend the subjective experience of another being, particularly not an animal that uses a sense so foreign to us. And it’s the same with emotion. While we share much in common with the animal kingdom, and we can observe and attempt to interpret behavior, we can never truly understand how another creature feels.

Because of this, every animal portrait involves the risk of anthropomorphizing and projecting our own feelings onto our subjects. And yet, I would argue that the impact of this basic truth on a photographer’s creative process is largely unimportant. “The artist is a receptacle for the emotions that come from all over…” said Picasso. “From the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web.” As photographers, our own feelings toward our subjects provide us with powerful and legitimate ways of interpreting the natural world—so long as we don’t deliberately misrepresent the situations we photograph. If we observe animals closely, register our feelings at the moment, and convey those feelings honestly through pictures, we can produce wildlife images that are rich with emotion and compassion. As Matisse put it, “I do not literally paint that table, but the emotion it produces upon me.”

The onus falls on us as photographers to capture and convey genuine feeling in our pictures, whether the emotion is felt by us or inferred from our subjects. An animal’s carriage and posture relay information about complex attitudes like confidence, irritation, or apprehension. An image of a lion in motion conveys more energy and power than a static pose, and catching the moment at which a foreleg is extended with forefoot uplifted communicates strength and impulsion. If at that moment the lion has a still-living impala in his jaws, the picture might send a crawl of gooseflesh across one’s arms in primal recognition of an apex predator.

Interactions between animals are packed with emotional potential. Play, predation, courtship and parenting manifest and evoke strong feelings, and it’s in these situations where facial expressions, posture, distance and contact convey powerful stories about relationships. These are dynamic situations in which behavior changes so rapidly that the conscious mind barely registers one event before something new happens. While photographing Northern elephant seals at Año Nuevo, near my home in northern California, I am struck by the watchfulness of bulls as they gauge one another’s size and strength, and by the shock in the eyes of a bull hit with unexpected force by an opponent. California sea lions, in contrast, have a comically intense sociability: they pack together, jostle for space, bicker with their neighbors. Each face is distinct—inquisitive, aggrieved, lethargic, or content. I am also drawn to the mixed emotions of a failed hunt: the dejected hunter, resigned to hunger, and her intended prey, winded, edgy but unscathed. In each of these cases, animals convey their stories through their bodies, faces and relationships. We viewers translate these into mood and feeling, and that connects us to the image.

In environmental portraits of wildlife, animals are embedded in their habitats—the mountains, plains, rivers, ice and oceans that support existence. Here, the skills of the landscape photographer are key: light, color, and composition convey a core mood; in some ways the wildlife are icing on an already rich cake. In others, animals are a focal point even if their representation is at first glance just a small part of the picture. In Namibia, I photographed zebras trudging steadily across an open plain. The simple geometry of the zebras and their determined but weary affect are set against a flat, almost two-dimensional image of vast space and blue sky. This isn’t a traditional landscape—without the animals, there is no photo. With them, the picture tells a story about vulnerability, exposure and purpose.

The mood of wildlife images can be shaped by conditions like fog, dust, or night. While searching for tundra swans in the rice fields of the Pacific flyway, I was ecstatic when morning sun dissolved into fog. Two swans met in the water, necks arched in feeding. In the fog they created a romantic portrait of intimacy. Yet here you ought to object and point out that this romance is a creation of the human mind. The birds were feeding, not courting. True—and yet the image genuinely relates my entrancement with the swans, and probably reveals more than I’d planned about the ardent romantic in me. The scene evokes a sentimentality unfelt by the birds, but one that reflects my (our?) fantasies about love and relationships.

Indeed, one’s own feelings are a deep reservoir of concepts for images. It takes only a few seconds to connect a feeling to an idea, then translate that concept into settings on the camera. Among the photos I’ve taken, a deliberately blurred image of a lioness is a favorite. I’d been startled by her appearance a few feet away, and the confusion, excitement, and apprehension I felt were echoed in her reaction to me. The image tells a story about a few seconds when my heart started to pound and primitive parts of my brain urged me to leap to the other side of the doorless Land Rover and into my lap of my guide. But the photographer in me insisted, “No, take the picture.” I wanted to connect all of these feelings—mine, the lioness’s, eventually the viewer’s—and convey the all-too-closeness of this moment. My fingers made a few adjustments and then, but only then, I took the shot.

Pushkar Joshi

21 Mar 2015Beautiful and insightful blogpost.

A question: When your subject is dynamic, do you have time to plan and think about what you would like to convey through the image, or is it that you capture what you can, and then retrospectively choose the narrative?

Susan McConnell

21 Mar 2015Thanks for the question, Pushkar! Even when there is intense action, I try to think and rethink the shot. I might first try to freeze the action, then switch my settings to generate blur. I often shoot with two cameras – one with a telephoto and the other with a wider angle lens – and between the two to generate different perspectives. Obviously if the action lasts only a few seconds, one may have only one chance to create an image (I have a “default setting” on my camera that allows me that chance). But often behavior lasts for several minutes, sometimes longer, affording plenty of time to rethink the image and my intent. That said, even as I try to plan and think, sometimes the resulting image surprises me and becomes something different than what I’d intended. That’s fine too!

Robert Kok

22 Apr 2017Beautiful site and stunning wildlife photos. Admire your work and dedication!